|

How to Stay Fit and Active as You Grow Older Fitness is not just for the young

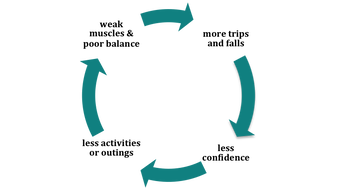

- walking on uneven surfaces? - climbing up stairs? - getting out of a chair Why Strength and Balance Matters There are many reasons why we can lose strength and balance - the most common is lack of use. As we get older we are less vigorous, less adventurous and less active, so we don’t challenge our sense of balance as we did when we were young. Therefore we:

We need to avoid the disuse cycle Your sense of balance can be influenced by:

Be sure you stay on your feet. Remember if we don’t use it – we lose it As you grow older you need:

Consider seriously increasing your level of fitness or activity even if your strength and balance and general fitness is still good.  Exercise Classes Find an exercise class that suits you, something that:

If you join an exercise class and:

Other recreational or sporting activities you may enjoy:

Visit ‘Active Canterbury’ and ‘Sport Canterbury’ websites for a list of activities in your area. Some general tips on exercise:

Physical activity is the best medicine for our bodies so keep it up as you age and enjoy it. If you need some advice about what exercise is best for you our friendly physiotherapist can help, just contact us on:  How fit am I? As we grow older our strength, balance and general fitness is in danger of declining so much so that we put ourselves at risk of falls, something we all wish to avoid. If you want to know how fit you are and to test your balance here a few tests you can do yourself. Walking distance – are you able to comfortably walk:

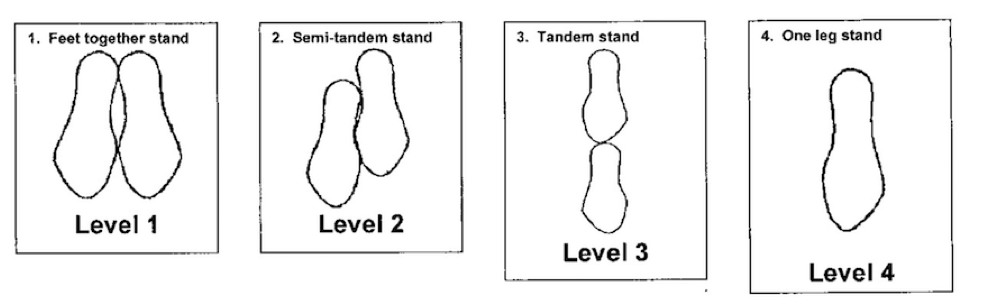

Not being able to walk round the block from your home is one indicator for increased risk of falling. Get up and go test – start by sitting down on a dining type chair. Record how long it takes you to: rise to standing walk three metres (10 feet) turn walk back sit down Try it again in a month’s time. A change of result by more than four seconds can indicate a change in the level of mobility. eg six seconds slower - weaker/less confident mobility six seconds faster - stronger/more confident mobility which is what you want Balance test This test has four levels of increasing difficulty and should be done without assistance. We advise you have someone with you while you do the test.

Scoring - Note down how long you hold each position Your score Level 1 Feet together stand / 10 seconds Level 2 Semi-tandem stand / 10 seconds Level 3 Tandem stand / 10 seconds Level 4 One leg stand / 10 seconds Total / 40 seconds Score of: under 20 seconds very poor balance 20 – 30 seconds poor balance 30 – 35 seconds moderately good balance 35 - 40 seconds good balance  Leg strength test Level 1 stand up with arms crossed if possible or use a hand to push up or use two hands to push up Level 2 stand up taking 5 seconds from when your bottom is off the seat Level 3 sit down taking 10 seconds until your bottom touches the seat Level 4 sit down, stopping half way down, hold 5 seconds, then continue to sit Level 5 sit down stopping about 5 cm from the seat, hold 5 seconds, then continue to sit Scoring Your score Level 1 Stand and sit arms crossed 5 points / 5 one hand to push up 3 points / 5 two hands to push up 1 point / 5 Level 2 Stand taking 5 seconds (score number of seconds held) / 5 Level 3 Sit taking 5 seconds (score number of seconds held) / 5 Level 4 Sit and stop half way down – hold 5 seconds (score number of seconds held) / 5 Level 5 Sit and Stop when about 10 cms from the seat – hold 5 seconds / 5 Then continue to sit (score number of seconds held) Total / 25 Score of: under 10 seconds very poor leg strength 15 seconds poor leg strength 20 seconds moderate leg strength 25 seconds good leg strengths 40 seconds good balance If you scored poorly on any of these tests, it’s time to take action!!

See our How to Stay Fit and Active as You Grown Older information page. Our friendly physiotherapist can help just contact Therapy Professionals Ltd on Phone: 03 377 5280 Email: [email protected] Financial support for those caring for a disabled person (from Ministry of Health Website) If you have an elderly family member or disabled child you care for at home and you need some time off the Ministry of Health can help fund some support (Carer support) for you. You may be able to use this support to fund some allied health services. Talk with your local DHB Needs Assessment and Service Coordination (NASC) services or Ministry of Health NASC Lifelinks in Christchurch. Carer Support Carer support provides reimbursement of some of the costs of using a support person to care and support a disabled person. This means their carer can take some time out for themselves. What Carer Support is Carer support is a subsidy that helps you take some time out for yourself. It provides reimbursement of some of the costs of care and support for a disabled person while you have a break. Who can get Carer Support Carer support is available for full time carers - a full time carer is the person who provides more than four hours per day unpaid care to a disabled person, for example, the parent of a disabled child. The number of hours or days that Carer Support is funded for depends on your needs and those of the person you are care for. Who funds Carer Support Carer support for people with age-related support needs, mental health and long-term medical conditions is funded by district health boards. Carer Support for people with disabilities is funded by the Ministry of Health. Getting Carer Support You can be assessed by a Needs Assessment Service Coordination (NASC) organisation, or, undertake a review with you, usually after a year. You can find out more about claiming at Carer Support Claims or by talking to your local NASC. Tax Issues Carer Support payments may be subject to income tax. This will depend on your individual circumstances. You may wish to seek advice regarding tax issues from the Inland Revenue Department or, if you receive a benefit, from Work and Income New Zealand. Carer Support – funded by the Ministry of Health The following information applies if you receive Carer Support from the Ministry of Health. Carer Support from DHB’s is not affected. You must work within your current funding allocation. You can continue to spend your Carer Support on any disability support/service/item that:

You cannot use your Carer Support for the following:

What people can buy with Disability Funding: Ministry of Health Purchasing Guidelines

Published online 17 April 2018 This document describes what government disability support funding (funding) can be used to buy. It is for people using:

Disabled people who can make choices about how they use their funding are more likely to buy goods and services that make their lives easier and/or better. This purchasing policy aims to give disabled people as much flexibility as possible over what they can buy with government funding. A disability support (support) is a good or a service that helps a person overcome barriers that come with having an impairment within a disabling society. Criteria There are four criteria that must be met to be able to use funding to help buy a disability support. 1. It helps people live their life or make their life better The support should help people live a good life. Each person has a different idea about what a good life is. The person’s goals and aspirations for a good life should be written out in a personal plan. This can be done with help from their Needs Assessment and Service Coordination (NASC) organisation or Independent Facilitator. Personal plans should include goals such as:

2. It is a disability support The support:

3. It is reasonable and cost-effective Generally, the support should be ‘reasonable’. Here it means that the support should cost about the same as (or less than) the market price for comparable things. ‘Cost-effective’ here means the best available outcome for the money spent. It might cost more than another type of support but will help the person more, it will last longer or mean that less is spent on some other support now or in the future. 4. It is not subject to a limit or exclusion A person should explore other funding options to help get a support. Examples of other options include:

In some cases, people can buy a support when funding for that support has been turned down by (or on behalf of) the responsible government agency or if waiting times are too long and the proposed support is expected to:

The funding cannot be used for:

Further help For more help in understanding this policy, people can talk to their NASC organisation or their provider to work out if a support they want to buy meetings the criteria. See Ministry of Health Purchasing Guidelines Processes Ministry of Health Purchasing Guidelines notes A Guide for Carers - He Aratohu mā ngā Kaitiaki Has a good summary of financial support available to carers https://www.msd.govt.nz/what-we-can-do/community/carers/guide-for-carers/index.html Reference: See Ministry of Health Carer Support https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/services-and-support/disability-services/types-disability-support/respite/carer-support What is Dementia? (By Dementia NZ 2017) Dementia is a progressive disorder where there is a decline in a variety of mental functions. The declining functions are primarily cognitive, that is, the person has a change in thinking abilities. The word dementia is a term which covers a group of disorders of cognition. Different types of dementia have different underlying disease processes and usually present with a different pattern of cognitive symptoms. However, all forms of dementia are associated with a decline in the ability to function day to day, emotional distress or behaviour changes. This will discuss:

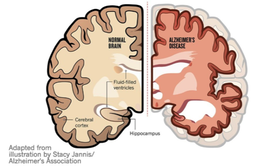

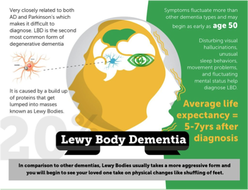

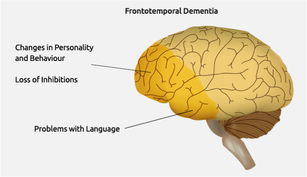

Types of Dementia Alzheimers Disease This is the most common form of dementia. It usually begins with a decline in memory and the ability to learn new things. Later, in the course of a steady, gradual deterioration, there are problems in other areas (for example speech, planning or reasoning, recognising objects, changes in emotions and behaviour). The cause of Alzheimers Disease is unknown though old age and certain genes appear to make people more prone to it. In the brain, there are microscopic changes, “plaques” of a substance known as amyloid and “tangles” within dying nerve cells. Vascular dementia: This occurs when there is insufficient blood supply to the brain. The symptoms are variable depending on which part of the brain is affected, though changes in the ability to pay attention, slowing of thought and frontal-lobe changes (see below) are common. The progression may be steady if the blood supply is gradually reduced by the narrowing of small arteries. Alternatively sudden or, “stepwise” progression occurs if the blood supply suddenly closes off to an area of the brain, often because a blood clot has formed or been carried from another location. The diagnosis is made from the history and evidence of blood vessel damage e.g. previous stroke seen on a brain scan or heart attack. It is quite common especially in the very elderly to have “mixed dementia”, that is, both Alzheimers and vascular changes.  Lewy Body Dementia (LBD): This condition is the third commonest cause of dementia, perhaps 20% of dementia cases. LBD is on a spectrum that includes Parkinson’s disease and the dementia associated with that condition. People with LBD have symptoms similar to those of Parkinson’s disease, such as stiffness, shaking and changes in gait. Cognitive changes include poor attention, changing levels of alertness and visual hallucinations (that is, seeing things that are not there). Sometimes those with LBD fall, faint or thrash about in their sleep as if acting out their dreams. Memory is typically not too impaired early on, but as the condition progresses all aspects of thinking are more widely affected. It is important to make the diagnosis to distinguish it from delirium, a potentially treatable medical condition, and to ensure the person is not given antipsychotic medication which can have severe side-effects in LBD. In this condition we see large spherical protein deposits in the brain – these are Lewy Bodies. The cause is unknown.  Frontotemporal dementia: In this group of conditions the frontal and /or temporal lobes of the brain are affected. Memory loss and learning problems are less obvious early on and the main symptoms are changes in behaviour and / or personality and / or language. The sorts of behavioural changes seen are: disinhibition (e.g. unrestrained or antisocial speech or behaviour), apathy (not initiating or doing anything), loss of empathy (understanding of others thoughts or feelings) repeated behaviours or rituals, changes in eating and loss of ability to plan or make judgements. Language changes include slow or hesitant speech, word-finding, naming, grammar and word comprehension. Frontotemporal dementia is a common cause of early onset dementia (beginning before the age of 65) and about 40% of people with frontotemporal dementia have a family history, suggesting there is a genetic cause. Who gets dementia? The likelihood of getting dementia increases as a person ages. This doesn’t however, mean that younger people – people aged less than 65 – don’t also get dementia. Some people may be predisposed to dementia by pre-existing intellectual disability, head injury or family history. Dementia is very common and as our population ages it is likely that everyone will have contact with someone with dementia. So the answer to “who gets dementia?” is really, “Anyone, though it is much more likely in older people”. How do you recognise dementia and get assistance? The important thing to note is that a person developing dementia has a change in how they function. For example, if someone has always had trouble reading maps or finding their way around and still can’t do this, there is no cause for alarm. On the other hand, if someone normally good at navigating, starts getting lost, you might worry. Sometimes the change is subtle: the usually reliable person is not paying the bills or the meticulous dresser goes out with stains on her clothing. This might not mean dementia. Other conditions like depression or physical illness can cause these changes, hence it is important to get to the doctor and / or encourage someone with alterations in their thinking ability, behaviour or emotions to attend the GP. In New Zealand the GP has access to a “cognitive impairment pathway” which is a series of steps and tests to go through to rule out other problems and decide whether this is dementia. Sometimes it is hard to tell and the person might be referred to a specialist (usually based in a hospital) or a memory clinic. Treatment

While there are no cures, yet, for any of the common forms of dementia, there is a lot that can be done to help and possibly slow the progression of symptoms. There is evidence that if people get an early diagnosis and thus know what is happening, they and their family / whanau cope better in the long term. Knowing what to expect also allows people to plan for the future. If you require some help managing a family member with dementia our friendly therpaists ca help. Just contact: Therapy Professionals Ltd Phone: 03 377 5280 Email: [email protected] Reference: Dementia NZ https://dementia.nz/wpcontent/uploads/2020/02/about_dementia_1_what_is_dementia_nz.pdf  Understanding Autism – Autism NZ Definition Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects cognitive, sensory, and social processing, changing the way people see the world and interact with others. Autism is currently estimated to be present in 1 in 54 people. It is not a mental illness, but a neurological difference - one of many variations of neurodiversity. Every autistic person is unique, with a wide range of skills, qualities, interests, and personality styles. As the saying goes, "if you have met one person with autism, you have met one person with autism." The level of support required is also highly individual. This heterogeneity is due to the fact that autism is not a single condition but a cluster of underlying neurological differences that are present in varying combinations in each person. The behaviour and needs related to these differences share common themes but manifest in different ways for each individual. Autism is considered an invisible disability since challenges and difficulties are often not immediately apparent. There are no visible physical markers. The cognitive differences associated with autism may also contribute to specific skills such as superior visual memory, attention to detail, and pattern recognition. Traits and characteristics An autistic person may experience challenges with social communication and interaction, have intense interests and a strong need for routines and predictability, and be hyper or hyporeactive to sensory input. No two autistic people are alike, but can often experience difficulty with social skills and executive functions, and have sensory needs that are different from those of the neurotypical population. Within these areas of challenge, autism will be expressed in different ways for each person, e.g. difficulty making small talk or having a balanced conversation, sensitivity to certain sounds or textures, and the need to stick to a daily routine. The traits experienced may change during the lifetime of a person as coping mechanisms or compensation strategies are learned and appropriate support is provided. However, this does not mean that the person has grown out of their autism. It would be more accurate to say that they have 'grown into' their autism, a process that is never finished and requires a phenomenal amount of energy to maintain. Many of the challenges autistic people face are not self-perceived as 'symptoms' of their autism but as difficulties created by their environment: a society that largely refuses to make accommodations for people with cognitive/invisible disabilities Reference Autism NZ https://www.autismnz.org.nz/what-is-autism/ |

AuthorShonagh O'Hagan Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed