|

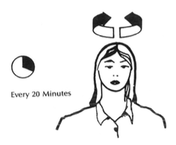

Social influencers: What makes good acoustic design for hard of hearing? Nobody likes being left out of the conversation, to feel like thery are not important enough to be considered and included.  Yet this is the sad reality for many older people who struggle with retirement villages or aged care homes that have poorly-planned social spaces. That is why the National Foundation for Deaf and Hard of Hearing (NFDHH) is calling on facilities -new and older -to consider their residents’ needs in social situations. “Like going to a noisy restaurant, often rest homes can have people talking at increased volume, there’s activities on, it’s by the kitchen – all adding up to a scene older people want to avoid,” Natasha Gallardo, chief executive of NFDHH says. “It’s important to create spaces that work well for people with hearing loss, and that communal areas are designed for their needs, because research suggests being socially isolated and lonely may put them at a higher risk of depression, cognitive decline, neurological issues and other health conditions.” More than 332,000 people are aged 75 years-plus, according to Statistics NZ. A 2017 NFDHH report – Listen Hear New Zealand – identified that 84 per cent of men and 77.6 per cent of women aged 75+ having hearing loss, 42.2 per cent of men and 34.4 per cent of women having moderate hearing loss. A hearing aid wearer herself, Natasha says that COVID-19, and the need for people to wear masks has exacerbated the feeling of exclusion and isolation for people who are hard of hearing and rely on lip reading and facial expressions as clues to help them understand what is being said. “Facing so many barriers to be heard and understood can be a real deterrent to socialising.” Natasha says. “If you’re a resident in a retirement home or aged care facility, and there are noisy common areas that are vacuous and echoing, the struggle is heightened resulting in people retreating. “Large communal spaces that have little sound absorption can make socialising far too challenging if you are hard of hearing. And as a result people become introverted and isolated. It’s not a good mix. “Tackling anit-social spaces in communal areas is a big issue right now. I’m getting emails from residents and elderly groups, wanting to lobby retirement villages to imporve the acoustics in the community areas. Minimising the background noise is a key for many, not having ways to sit in smaller configurations that are facing each other is another.” An important elelment of retirement village life is encouraging people to keep active and to join in and do things together. But that can mean en-masse gatherings. Natasha says the principles of shared office spaces being constructed with a multitude of needs, are concepts that would also work well in retirement villages. By 2048, the number of people aged 75-plus in New Zealand is projected to grow to 883,000. More than 47,000 people live in a retirement village, with a large number of new properties being built to meet anticipated demand.  But for existing properties, she suggests simple changes to help hearing aid wearers:

“We aren’t suggesting elderly residential properties should be sterile and devoid of music and other sounds – but just that there are areas people can still congregate and catch up with others where it’s quieter. These community spaces must still be the heart of their home, welcoming and enjoyable.” Home care help for hard of hearing Discovering how social your home care clients are can be a key to ascertaining how they are managing their hearing loss. “Even as an informal chat can identify whether people are going out less, if they are avoiding social situations -and it gives you a conversation starter, to check on why,” Natasha says. “The COVID-19 pandemic makes people reluctant to go out, particularly if they struggle to understand people talking while wearing a mask. So clients may also be putting off having simple hearing aid checks, but these are vital.” She recommends making notes on the level of volume you need to use when talking to clients, to be understood, and if you notice that deteriorating between visits, suggest they see an audiologist. Another sign that a person’s hearing is deteriorating is the volume on their TV or radio, so keeping a record of that can also alert home care staff to issues. “Often elder clients are not savvy with new technology, so when checking TV volumes, look to see if they have enabled captions, to help them watch their favourite shows.” If you have time during your appointment, ask when they had their hearing aid batteries checked, or do they need repairs. “These are often questions that family and friends don’t ask, so simple check-ins like this could make all the difference.” How to tell if someone may have increased hearing loss:

For more information visit the National Foundation for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing website: www.nfd.org.nz Aged Care New Zealand Issue 02 2022 Managing Long COVID in Aotearoa New Zealand physiotherapists have been working closely with their counterparts overseas to find out more about Long COVID and how best to support those suffering long-term effects.  Research shows that as many as one in eight COVID-19 patients could get Long COVID, which means there are likely hundreds of New Zealanders still experiencing symptoms 12 weeks after testing positive. Physiotherapy New Zealand (PNZ) spokesperson Dr Sarah Rhodes says it is understandable that patients with Long COVID are increasingly frustrated that their recovery is so slow as the symptoms can persist for months and years in some cases. PNZ calls on the government to support people’s access to effective treatment for Long COVID, just as they have supported people through the pandemic. “We know that COVID-19 affects people differently and it is the same with Long COVID. It doesn’t only affect those who are hospitalised with an acute COVID infection. It can also affect those whose initial symptoms are mild and even those who are asymptomatic with the acute COVID-19 infection.” “The desire to get back to normal life after COVID-19 is understandably important for all of us. With today’s busy lifestyles, it’s often hard to be that person who needs to rest instead of going back to work, getting back into your leisure activities, and looking after children and/or older family/whanau members. However, rest is an essential part of managing an acute COVID-19 infection as it is likely to reduce the risk of developing Long COVID,” says Dr Rhodes. Members of PNZ’s Cardio-Respiratory Special Interest Group have developed some general tips to help guide people through a prolonged period of symptoms. Fatigue This is the most common symptom of Long COVID. Undertaking daily activities which were easily managed prior to COVID-19, such as showering, can be exhausting.

Breathlessness Breathlessness is another commonly experienced symptom in those with Long COVID.

Muscle and joint pain

Return to exercise

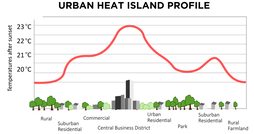

Physiotherapy can help manage symptoms of Long COVID. However, for some patients a multi-disciplinary approach, involving other health professionals, is recommended. Aged Care New Zealand Issue 02 2022 Climate explained: How white roofs help to reflect the sun’s heat Does the white roof concept really work? If so, is it suitable for New Zealand conditions? Generally, white materials reflect more light than dark ones, and this is also true for building and infrastructure. The outside and roof of a building soak up the heat from the sun, but if they are made of materials and finishes in lighter or white colours, this can minimise this solar absorption. During the warmer part of the year, this can keep the temperature inside the building cooler. This is especially important for building and construction materials such as concrete, stone and asphalt, which store and re-radiate heat.  A New Zealand study tested near-identical buildings in Auckland with either a red or white roof. It found that even in Auckland’s temperate climate, white roofs reduced the need for air conditioning during hotter periods, without reducing comfort during cooler seasons. The study also identified several large-scale white-roof installations, including at Auckland International Airport, shopping centres and commercial buildings, but the effect was less clear. This research suggests that there is potential for white roof installations to significantly reduce the amount of energy needed to cool buildings. This would in turn reduce greenhouse gas emissions and also help us to adapt to rising temperatures. It is difficult to quantify the impact for New Zealand’s housing stock because existing studies are mostly limited to larger commercial buildings. But research carried out so far suggests white roofs could be a viable approach to minimising the heat taken up by buildings during hotter parts of the year.  Cooling cities White roofs can also help reeduce the temperature of whole cities. Many city centres include large buildings made of concrete or other materials that collect and store solar heat during the day. In a phenomenon known as the “urban heat island” effect, city centres can often be several degrees warmer than the surrounding countryside. When cities are hotter, they use more energy for cooling. This usually results in more greenhouse gas emissions, due in part to the energy consumed, and contributes further to climate change. New Zealand is different because our land mass has a maximum width of 400 kilometres. This means that unlike many urban islands on the African, Asian or American continents, New Zealand’s city centres benefit from the cooling effects of being near the ocean. There are many international studies showing white roofs are effective in mitigating the urban heat island effect in densely populated cities. But there is little evidence that using white roofs in New Zealand cities could result in significant energy reductions. A growing number of studies suggest making the surfaces of buildings and infrastructure more light reflecting could significantly lower extreme temperatures, particularly during heat waves, not just in cities but in rural areas as well. A recent study shows strategic replacement of dark surfaces with white could lower heatwave maximum temperatures by 2°C or more, in a range of locations. But studies have also identified some practical limitations and potential side effects, including the possibility of reduced evaporation and rainfall in urban areas in drier climates. In conclusion, white roofs could be a good idea for New Zealand to keep homes and cities slightly cooler. As temperatures continue to rise, this could reduce the energy needed for cooling. We should consider this option more often, particularly for commercial-scale buildings made of heat-retaining materials in larger cities. Authors: Nilesh Bakshi and Maibritt Pedersen Zari Aged Care New Zealand Issue 02 2022 Exercises to help prevent Occupational Overuse Reference: Developed by Sentinel Supported by ACC

If you are experiencing pain or discomfort doing your job out friendly physiotherapists and occupational therapists can help. Just contact us Phone: 03 377 5280 Email: [email protected] Physios key to shorter waitlists (Article from The Press, January 19, 2024)  Lynn Downes doesn’t need prompting to get up and dance. The 73-year-old has spent the holidays running around after her seven grandchildren despite, a year ago thinking she might have been facing a hip replacement about now. Downes had her right hip replaced in 2021, then her left side began playing up a year ago. “I thought, ‘Oh, gosh, here we go.’” It had taken two referrals from her GP in 2021 before she was scheduled for surgery. Her pain had worsened, and she didn’t fancy joining the treatment queue again. That queue has been an ongoing headache for Te Whatu Ora-Health NZ. As of November, more than 1500 people had been waiting more than a year for orthopaedic treatment. Traditionally, the standard treatment process meant a patient referred by their GP went straight to an orthopaedic surgeon to be assessed. Now a Wellington pilot allowing orthopaedic physiotherapists to assess patients in the first instance has reduced treatment times by an average of 75 %. In Wellington, patients are now waiting an average of 40 days for an initial spinal assessment, rather than 180 days in December 2019, while hip or knee complaints are being assessed in about 45 days. In August 2021 these patients were waiting 165 days. Downes admits she was sceptical of the approach at first, but the exercises have allowed her to sleep without pain and keep pace with her school-aged grandchildren. “She went over my history, the X-rays…She gave us some exercises and a pathway so I could contact her if my symptoms got worse,” Downes said. “It’s a much better route. If things got worse, the physio would then contact the surgeon.” Her treatment is ongoing, but she said she hoped to avoid surgery. In Wellington, the pilot has been led by expert physiotherapist Sarah Francis, who said more than 600 patients had been through the programme since September 2022, at Wellington and Kenepuru hospitals and Kāpiti Health Centre. Of course in some cases, surgery would be unavoidable, Francis said. But there was no need for every patient’s first assessment to be done by a surgeon. “Part of this project is about making sure people get non-surgical care earlier. The sooner we intervene for people with, particularly conditions like osteoarthritis, we can prevent progression to joint replacement,” Francis said.  Patients were happy, too – 86% felt confident in being assessed this way, and fewer than 5% were referred back into the system after one year. Last August, Te Whatu Ora said it wanted to treat all orthopaedic patients who had waited more than a year by June 30. This was still the goal, planned care and cancer programme director Ian D’Young said, and good progress was being made. It was forecast that more than 14,000 patients were in that category, and by December 3 that number had come down to 5,222, he said. But for some it’s too late. Wellington man David Garlick, 25, was turned away from the public system after two years of bouncing around appointments seeking help for a condition causing painful excess bone growth on a femur. For him, surgery was unavoidable, but the time spent languishing in the public queue meant his condition worsened, taking an enormous toll on him and his fiancé. “It was a waste of my time, their time, everyone’s time.” It also left him facing $30,000 private medical bill, only avoided after a surgeon from the Auckland-based Aotearoa Charity Hospital read about his ordeal in The Post and offered to operate for free. Garlick now needs the same surgery on his other hip, which he also hopes to get done through the charity hospital. D’Young said Te Whatu Ora appreciated the impact of treatment delays “and we are working hard to put in place systems and processes so improvements to waiting times are made”. Author: Rachel Thomas, The Press, 19 January 2024 |

AuthorShonagh O'Hagan Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed