|

Home Gym Fitness - part of everyday life  Kitchen Bench Exercises – hold the bench if necessary

Hallway Exercises

Bathroom Exercises

Posture check!

Lounge Exercises

These can be done with a weight on the ankle [for thigh muscles]

Bedroom Exercises

These exercises are designed to increase strength and improve balance. Do them within your limit of comfort – they SHOULD NOT CAUSE PAIN.  DiningRoom/KitchenExercises

Repeat 5x. Work up to 20x for leg and buttock muscles Leg Weights Exercise for thigh muscles Sit on dining chair – wrap weights round ankle Start with:

Progress to:

Further progression:

Note:

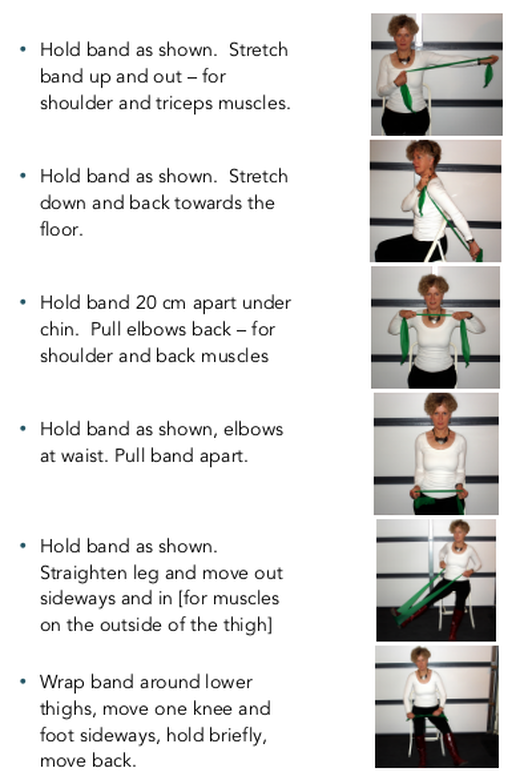

Band Exercises

Sitting – before lunch exercises Do each exercise slowly – control the stretch and release part of the movement.  History of Music Therapy in New Zealand From the Music Therapy NZ website The beginnings “Several historical threads interweave the beginnings of a national body for professional music therapy. Individual musicians, from the late 1950’s, were using music therapeutically- Warren Green (Otago), Marie O'Brien (van Asch College Christchurch), Ariadne Danilow and Judith White (Wellington), Lu Quin (Rotorua), Margaret Knight (Tokonui Hospital), Mary Edwards (Homai College Auckland), Marie Franklin with Eleanor Rose and a team of volunteers (Kingseat Hospital (Auckland). In 1974 Marie Franklin and Eleanor Rose, with audiologist Dr Bill Keith, brought pioneer music therapists Paul Nordoff and Clive Robbins to New Zealand to run main centre workshops on working with children with hearing impairment and learning disabilities. This initiative was a major contribution to the understanding and development of music therapy in Aotearoa New Zealand. About the same time a budding concert pianist, Mary Lindgren, who had gone to the UK from New Zealand for further piano study, met pioneer Juliette Alvin and was invited to join to Alvin’s music therapy trainee/practitioner course, the first of its kind in Britain. This she did, and became determined and energised to encourage music therapy as a profession in her home country. Her 1974/75 visit was therefore driven by that goal and was a major factor in the establishment of the New Zealand Society for Music Therapy in 1975. We honour her name and pioneering work through one of our grants, the Lindgren Project F 1974 New Zealand Society for Music Therapy (NZSMT) established The NZSMT was founded as a charitable organisation, with the aim of raising awareness and provision of Music Therapy and support for the emerging profession. 1975 Sir Roy McKenzie Another key figure from this era, philanthropist Sir Roy McKenzie, became a significant supporter and benefactor from these early days until his death in 2007. The McKenzie Scholarship and McKenzie Music Therapy Hospice Fund were established with donations from Sir Roy and are named in his honour. Sir Roy giftedMThNZ shares in Rangatira several times, readily responded to requests for urgent financial support, but also gave financial advice and always came to special events. The organisation would not have begun, nor would it be in the position it is today, without the significant contributions of Sir Roy. 1975 – 2000 Raising the profile of music therapy NZSMT works to raise the profile of Music Therapy in New Zealand: publishing newsletters, establishing the Annual Journal, and lobbying politicians and policy makers in health, education, justice, welfare and community (Croxson, 2001). The society, through the significant time and energy of many individuals, brings international Music Therapy clinicians, researchers and educators to NZ for training courses, conference presentations, workshops and professional development courses (Croxson, 1993, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2007; Krout, 2003). Professional association established The New Zealand Association for Music Therapists (NZAMT) is established (with branches in Wellington, Manuwatu, Auckland, & Christchurch) alongside the existing NZSMT, with the following aim: [To] develop and maintain professional standards in Music Therapy in New Zealand, provide input into Music Therapy training programmes, ensure that a high standard of supervision was maintained, and to link with other relevant associations as appropriate. Activities included professional development days, the development of a Code of Ethics and work towards Standards of Clinical Practice for Music Therapists, job descriptions and register/s, pay scales, copyright documents, professional indemnity insurance, and the development of a Music Therapy training programme. (Rickson, 2014) 1995 NZSMT established the New Zealand Music Therapy Registration Board In order to be registered, a Music Therapist needs to have completed a recognised Music Therapy training, adhere to a Code of Ethics, and engage in ongoing professional development and supervision. While the NZ Music Therapy Registration Board operates independently of Council, it remains a function of Music Therapy New Zealand and continues to be underwritten by the society. 2000 Masters of Music Therapy Course After 18 years of effort, politically and financially, the first tertiary course in Music Therapy was approved in 2000. Barbara Mabbett, Natali Allen and Morva Croxson drew up the documentation and curriculum for the course through the Education Committee which Natali, a nurse, Chaired. In 2002 the first programme leader, Dr Rober Krout, was appointed, and in 2003 the Master of Music Therapy (MMusTher) programme enrolled its first students at the Wellington campus of Massey University, and was then absorbed into New Zealand School of Music (NZSM), a collaboration between Massey University and Victoria University of Wellington (VUW) (2005 to 2015) and now part of VUW alone. The current course is taught by Dr Sarah Hoskyns, Director and Associate Professor, and Dr Daphne Rickson, Senior Lecturer. For more information about the course, please refer to the University of Victoria website.  2000 – 2003 RMThs, Specialist Service Providers NZSMT successfully advocated for RMThs to be listed as service providers in the Ministry of Education’s Specialist Service Standards for students funded through the Ongoing Resource Scheme (ORS). Early 2000s First Music Therapy Centre founded NZSMT provides the first seeding grant in support of Raukatauri Music Therapy Centre (RMTC), the first (and currently only) dedicated Music Therapy centre in New Zealand. Founded by Hinewhei Mohi in 2004, in collaboration with Campbell Smith, Boh Runga and other local music industry people, RMTC is a charitable trust that provides Music Therapy to children and young people with special needs. 2004 Unifying the organisation NZSMT rebrands as Music Therapy New Zealand (“MThNZ”), our new trading name, with a new logo, a website, and shortly afterwards an online forum for Registered Music Therapist members. NZAMT, regional branches, were brought together to form one national body with the aim of creating a more unified and economically viable organisation. It was also an acknowledgment that the profile of NZSMT membership was shifting from being predominantly friends and supporters of Music Therapy to mainly professional Music Therapists (Rickson, 2014). Governance and general promotion of Music Therapy is delegated to the Council. NZAMT is replaced by the Education Training and Professional Practice group (ETPP), with a forum of seven elected RMTh members whose role was to manage all aspects of professional development and liaise with the National Executive, tertiary providers and the Registration Board. 2005 AHANZ members Following significant consultation regarding the HPCA Act, MThNZ joined and became active in Allied Health Professional Associations Forum (AHPAF), later rebranded as Allied Health Aotearoa New Zealand (AHANZ). 2010 Restructuring For a number of reasons, the decision was made for the Society to discontinue the professional development activities, disband ETPP and amend the Rules accordingly, and undertake a re-visioning process which led to a restructure and the new Council and portfolio roles. New Zealand Society for Music Therapy continues to be the legal name for Music Therapy New Zealand (trading name). 2013 MThNZ Regional Groups established The intention for reestablishing regional groups are for ‘ground up’ advocacy, support & networking forums for all MThNZ members, as well as to create connections and grow relationships with related professionals and organisations in local areas. 2015 Increasing our reach MThNZ establishes itself within social media, creating a Facebook page that seeks to increase every New Zealander’s awareness and value of Music Therapy in its multiplicity of models, Music Therapy research, Music Therapy Week and other MThNZ events and activities. 2016 First ever Music Therapy Week MThNZ establishes the first ever Music Therapy Week, which aims to increase the awareness of Music Therapy and celebrate the Music Therapy that is happening throughout NZ in health, education and varied settings. It also provides a platform that aims to foster connections with other disciplines and ensure every New Zealander knows how to access a Registered Music Therapist. 2016 Looking to the future MThNZ rebrands and rebuilds their website, taking a giant step forward with the opportunities that advancing technology and communications enables for increasing awareness and understanding about Music Therapy as an allied health profession. Reference: Music Therapy New Zealand Website. https://www.musictherapy.org.nz Therapy Professionals Ltd has provided music therapy in Christchurch since 1998. If you have a child with a disability who’s struggling music therapy may help. Just contact us on: 03 3775280 Email:[email protected] Have you fallen or do you fear falling? Four easy ways to remain surefooted and safe everyday, from an 80 year old ex physio 1. Don’t rush

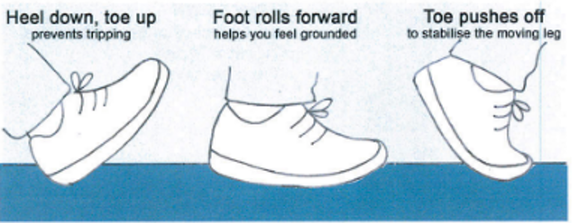

2. Be aware of heel-roll-toe As we get older we lose the spring in our step and the muscles that lift our toes weaken. We need to compensate for these losses and walk safely. Your feet matter Wear firm fitting shoes, sandals or bare feet. Feel the soles of your feet move inside your shoes. They will tell you:

Place feet slightly apart with toes slightly turned out. Exaggerate the natural heel-roll-toe action Practice heel-roll-toe whenever you walk

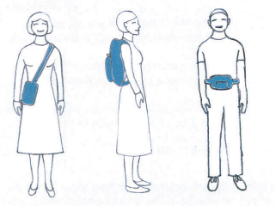

As many falls occur at home, heel-roll-toe is as important when you go from room to room as it is going from street to street. 3. Carry objects close to your body To maintain good posture when you carry objects, stand tall with your neck and shoulders loose. When walking and carrying:

If you must carry heavy objects, try not to hunch or lean towards the weight, even if it is on wheels. Keep tall and straight, then the weight will seem lighter.  4. Keep your legs strong Climb hills and stairs when available. Don’t always depend on sticks and handrails. If hills and stairs aren’t available, standing up from sitting is a great exercise for thigh and core muscles.  Stand up in three simple moves:

Sit down again in three simple moves: 1. Bring head and shoulders forward 2. Bend your knees 3. Gently lower In conclusion Establish these activities NOW, before you learn “special” balance exercises. These habits will be with you when you are past doing the balance exercises. They will be with you until the end of your life. Brochure designed by Siobhan O’Hagan and written by Clare O’Hagan.

Available from Therapy Professionals Ltd  Why are seniors always so cold? Winter may bring sparkling snow and for some, the holidays; but it also brings increased heath issues – especially for seniors. It’s a good idea to know what to look for and expect so that those you care for can stay healthy As people age, their bodies become more sensitive to cold temperatures. This is because of a decrease in the metabolic rate. Ageing bodies are not capable of generating enough heat to help maintain their normal temperature and thinning of the skin is another factor that may contribute to the ‘feeling of cold’ in older adults. The increased sensitivity to cold or feeling cold more than usual, can however, mean that the person is suffering from mild hypothermia. Hypothermia is a condition characterised by extreme low body temperatures. When the temperature of the body falls below 32 degrees, the body becomes so cold it starts to shut down. The National institutes of Health noticed that hypothermia is a less obvious danger for vulnerable adults that requires immediate treatment. Individuals who are older are at an increased risk of hypothermia because their bodies cannot withstand the cold as long as younger people. It’s also true that some medications and illnesses can further heighten this risk. Seniors naturally create less body heat, which means they are often colder than younger individuals to start with. Signs of hypothermia include slowed reactions and movements, sleepiness, slurred or slow speech and confusion. Wearing layered winter gear along with a hat, gloves and warm shoes can do wonders in preventing hypothermia. The home environment temperature should be set to 24 degrees Celsius or higher. Seniors may want to talk to their physicians about any medications or chronic health problems that could increase their risk of hypothermia. Heart troubles worsen According to the National Heart Foundation, seniors who have cardiovascular conditions may experience increased side effects in the cold. Because lower temperatures and winds can reduce body heat, blood vessels tend to constrict, making it more difficult for oxygen to reach the entire body. The NHF recommends that seniors where layered clothing to trap heat and provide insulation. Seniors who are thin are especially at risk of cold-related cardiovascular issues because they do not have as much fat to provide warmth and keep blood flowing.  Chronic pain often flares up It’s common for seniors to have chronic pain like arthritis. When it is cold outside, many people note their symptoms worsen. This can lead to taking excess pain medications, whether prescribed or over the counter. Seniors should talk with their doctor if they find their joints are more painful than usual. Physicians may recommend changing their medication or trying home remedies like Epsom salt baths to relieve the aches. Sleep habits are altered During the winter, the amount of sunshine is typically far less than during the rest of the year. This can make anyone feel sluggish and want to sleep more. Getting extra rest isn’t a problem until sleeping becomes a huge part of the day. Seniors may want to consider setting the alarm to wake up for breakfast and ensure they’re not staying in bed late because of the winter darkness. Keeping a regular schedule can be a big help in avoiding sundowners syndrome, as can opening the blinds and turning on the lights during the daytime. Sundowners syndrome, or sundowning, involves a pattern of sadness, agitation, fear, delusions and hallucinations that occurs in dementia patients in the late afternoon, evening and at night. This increased confusion around twilight can be distressing for both patients and caregivers alike. Falling risks increase Seniors who live in climates that receive snow and ice during the winter are also at an increased likelihood of falling. Those who live at home and do their own shovelling or yard work are especially likely to fall. However even individuals who reside with caregivers and walk with supervision may be at risk. Areas around the home should be shovelled and salted to prevent falls, and they should ask for assistance when required even if it’s just an arm to lean on when walking to the car. The elderly should consider using a walker to help them stay balanced while walking outdoors in the winter. Falling risks also go up indoors during the winter because melted snow on the floor can prove slippery. A senior who has been outside and become very cold may have reduced mobility and balance and can fall while moving indoors. Always check on seniors when the temperature dips or snow and ice are present.  Various factors that contribute to cold sensitivity include:

Medical Conditions contributing to being cold:

Signs of cold sensitivity:

How to keep seniors warm when they are cold:

Awareness and vigilance are important. Feeling cold even in the warm climates is a signal that a person should see a doctor. All the above-mentioned tips should help caregivers keep their loved ones warm. Article from Aged Care NZ Issue 02 2021 Managing difficult behaviours in dementia There are more than 78,267 New Zealanders with dementia, and 80 percent of them may develop behavioural symptoms such as aggression, hallucinations, or delusions at some point. Author: Linda Conti, RN, CHPN  As the geriatric population grows, health care practitioners will increasingly encounter distressed caregivers of dementia patients asking for help in handling difficult behaviours. Though most agitation is probably a result of deteriorative changes, health care professionals can influence behaviours. Ensuring needs are met using reassuring language, changing environments, and engaging in soothing activities are among helpful strategies for addressing undesirable behaviours. Agitation is the most common reason families place loved ones with dementia in nursing homes. Some experts suggest that all behaviours are forms of communication. So confounding or ‘bad’ behaviour may actually be an effort to communicate an unmet need when the disease has robbed a patient of words and logic. Resistance-type behaviours may be a response to loss of control, confusion about what is happening, or even feeling rushed in a particular situation. A patient may be depressed, in pain or responding to stress. There is supposition that as the nervous system degenerates, it leaves patients with decreased ability to cope with stress. Caregivers need patience and persistence to sort through patient’s behavioural clues. They should begin by ruling out straightforward physical factors such as pain, injury, constipation, infection, wet briefs, tight or uncomfortable clothes, or a patient feeling too hot or too cold. A patient may provide clues about an underlying problem. In one actual situation, a patient complained bitterly that his foot hurt. In the emergency department, an assessment revealed a severe bladder infection. Following treatment, the patient said his foot no longer hurt. He had provided the biggest clue – that he had pain and it was up to caregivers and healthcare professionals to find the source. Caregivers should review the events of the previous day to evaluate whether a patient may be fatigued from lack of sleep or whether there are changes to a patient’s routine or environment, including the presence of simple holiday decorations for example. Change is the enemy of dementia. Experts in the field of dementia have identified six situations that commonly spar agitation, including fatigue, change, a perception of loss, level of stimulation, excessive demands, and physical stressors such as pain, infections, or constipation. Difficult behaviours Agitation and aggression Agitation, restlessness, and anxiety are common in people with dementia, but even more worrisome is aggression. These behaviours can begin abruptly, or build from a patient’s frustration. They key to managing them lies in examining the source of behaviours to understand the feelings leading to the actions. After checking for physical discomfort, examine what happened immediately before the negative behaviour. What triggered it? Spending the time to figure this out may help prevent future incidents. Use a soft, soothing tone and reassurance in addressing the patient, such as “You seem upset. I’m sorry you’re upset but I’m right here. Let’s get a cookie”. Try a change of environment, something surprising or distracting: dancing, singing a song, going for a walk, or simply going to another room. Involve the patient in an art activity or ask for his or her help with a task. Go for a ride in the car. Play familiar hymns, Christmas carols, or old-time music. Keep in mind that reasoning doesn’t work. Wandering Nearly two thirds of people with dementia will wander at some point. Be prepared. A patient may wander when looking for someone ‘going to work”, relieving boredom, or looking for a place to eat. Identifying the reason for wandering may provide clues about managing it. Suspicion or paranoia This is a phase many people with dementia experience. They may believe someone is trying to steal their money or belongings. This feels very real to dementia patients; explaining and logic won’t work. This is a manifestation of the disease, and not the patient’s thought, it’s not personal. Let the person speak without correcting him or her, be reassuring, reminding him or her who you are and that you are here to help, using phrases such as, “Let me help you look for the money”, and then redirect attention to something else in the room. If money is a recurring issue, put coins and small bills in a purse or wallet for you to “find” in the future. If a person believes people are breaking into the house reassure him or her with statements such as, “That must be scary. I’m right here. I’ll make sure nothing bad happens.” Then refocus attention. Sleep issues Many people with dementia experience difficulty with their circadian rhythms that dictate sleep and wake states. Some tips too help normalise sleep habits include maintaining consistent sleep and daily routines; limiting daytime sleep to 15-20 minute naps; increasing daytime activity, including physical activity such as walking or dancing; avoiding caffeine or serving it only in the morning, offering a light bedtime snack to prevent hunger as a cause of agitation; allowing as much independence as possible in decision making, including a person’s most comfortable sleeping spot; considering melatonin to promote sleep, and keeping a night light on and the room uncluttered. Seek medical advice if these measures don’t work. There may be medical conditions contributing to the night-time confusion and agitation. A physician can also review a patient’s medications, limiting those causing reactions or that are unnecessary. Bathing For some dementia patients, bathing prompts agitation. It may feel strange to a person with dementia to have help with an activity he or she has always performed privately. Preparation can help enormously. Treat pain first. If the patient experiences pain with movement, medicate at least 30 to 60 minutes before the bath. Have at the ready all the supplies you will use. Explain what you are going to do and allay fears. Maintain modesty and ensure the room and water temperature are comfortable. Let the patient do as much as possible for him- or herself. Providing choices restores a sense of control at a time when the person has lost control of so much. Offer choices such as, “Would you like to wash your face or would you like me to help?” Maintaining regular routines, including a regular bath routine, is the key to maintaining serenity. Rushing or startling a person with dementia may provoke agitation. Communication Simple things can greatly enhance communication with a dementia patient. Focus on the communication style. Sit down, if possible, to be at a person’s eye level; standing over someone can feel threatening. If there is a chance the patient has forgotten who you are, introduce yourself. Use a pleasant voice with a smiling facial expression. Speak slowly, calmly, and clearly – not more loudly. Don’t argue or try to reason with the person; logic doesn’t work. Speak in short sentences, pausing after each to allow a person to process what you have said. Give one simple instruction at a time. When a patient with dementia is told “Put your shoes and socks, brush your teeth, comb your hair, and come to the kitchen to eat your breakfast”, none of those things may happen. Use hand gestures when possible, such as patting the chair in which you want the person to sit. Wait patiently for a reply before repeating yourself.  Delirium Delirium is characterised by a sudden change in thinking ability as opposed to the drawn-out disease process of dementia. Delirium is treatable and should be promptly addressed. If non-drug treatments fail, antipsychotics can be effective. Delirium is characterised by a sudden change in thinking ability, inability to focus or sustain attention, changed perception of surroundings, disorganised behaviour, variable or fluctuating status, and a sudden onset within hours or days. Delirium triggers include a new or changed environment, such as hospitalisation; electrolyte imbalance; faecal impaction; urinary retention; drug interactions or side effects; pain; stress; injury; or a serious medical problem such as a stroke, organ failure; or blood clot. As with agitation, delirium can often be prevented or reversed with a calm, familiar environment and routines, activity during the day and quiet surroundings at night, glasses and hearing aids that are working and in place and relaxation, such as music, massage, or reading to the patient. Solutions for dementia induced behaviours Bright light Exposing elderly adults with dementia to bright light boosts their mood. Circadian rhythms are very sensitive to light. Research has shown that nursing home residents exposed to bright light for nine hours per day experienced fewer dementia and depression symptoms. It also improved disturbed thinking, mood, behaviour, functional abilities and sleep. Adding melatonin reduced the time it took to fall asleep and increased the length of sleep in the study. However, when given alone, it made residents more withdrawn during the day. When used with bright light therapy, melatonin reduced aggressive behaviour and didn’t produce resident withdrawal. This research indicates that melatonin should be used only in conjunction with bright light therapy. Rummage bags People with dementia often feel a sense of loss – of objects, memory, and the ability to communicate. This sense of having lost something can cause anxiety or agitation. A rummage bag is a tool to occupy, distract, and satisfy a patient with dementia with an activity related to what they are feeling. It can also relieve boredom. Use a large purse, a men’s toiletry bag, or any other bag, with an assortment of familiar objects that might be interesting to touch, manipulate, or examine. It can easily be filled with common objects in the home. Be sure to avoid items small enough to swallow, sharp objects, or anything that can be disassembled. Be creative. A bag might include items such as keys, address book, wallet, unbreakable mirror, coin purse, small stuffed animal, sample credit cards, photos, TV remote without batteries, comb, old cell phone, sealed flashlight, or a bottle opener.  Distraction kit Create a bag or box of interesting, unexpected, and pleasant activities to introduce when you need to redirect a person’s attention. Eventually the box may have such pleasant associations that the patient quickly redirects his or her attention to it. It could include items such as aromatherapy or perfume; a sound machine with chirping, rain, waves, and other sounds; picture books; a music box; lotion for a hand or foot massage; a flannel basket to warming a dryer and wrap around feet; or special treats. Though none of these techniques will work all the time, patience, persistence, and trial and error can reduce agitation in dementia patients, significantly improving quality of life for both patient and caregiver. Author: Linda Conti, RN, CHPN, Director of marketing for Pathways Home Health and Hospice. Aged Care Issue 2 2021 |

AuthorShonagh O'Hagan Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed