|

The magic power of Diaphragmatic Breathing  Breathing happens automatically like other bodily functions, such as:

These functions are controlled by our autonomic nervous system, which has two parts. The sympathetic system, which usually gets these functions going and the parasympathetic system, which stops them from happening. The sympathetic controls our fight-or-flight response, while the parasympathetic is in charge of everyday processes. Even though these functions are automatic, we can help regulate our automatic nervous system, with diaphragmatic breathing. This has many benefits — your heart rate and blood pressure can be reduced, helping you to relax. This all helps decrease the amount of stress hormone, cortisol, released into your body. Diaphragmatic or tummy breathing also helps:

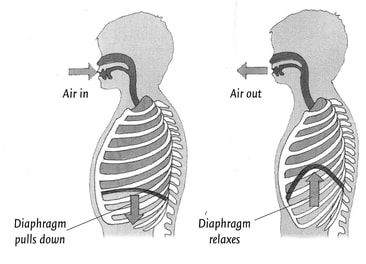

Many of us breathe only using our upper chest cavity and when we are asked to breathe deeply we pull our shoulders up and expand the upper part of our chests. Breathing in this way does not make use of the lower capacity of the lungs. Diaphragmatic or deep tummy breathing is named after the diaphragm muscle. This muscle pulls air down into the lungs (like bellows) and as it relaxes, it rises up and forces air out of the lungs. Learning to do diaphragmatic or tummy breathing takes time and conscious effort. Here are some instructions:

Practice tummy breathing regularly, eg when you first sit down to watch TV every night or before you go to bed. Once you've perfected the art you'll be able to use tummy breathing to calm yourself when you're under stress. If you are struggling to tummy breathe, just contact us we can help. Phone: 03 3775280 Email: [email protected] Practical perspectives on ambulation aids Choosing the best equipment, having it set up for you and being taught how to use it properly will help to keep you mobile and independent. This article explains a lot about mobility aids, however it is really important, especially if you have had a stroke or have some other neurological condition, to have an assessment by a physiotherapist. They will look at your physical capabilities, lifestyle, advise you on the type of equipment to best suit your needs, adjust the equipment and teach you how to use it safely and effectively. Our friendly Physiotherapist can help, just call us at Therapy Professionals Ph: 03 3775280 Email: [email protected] Selecting safe, effective ambulation aids for older adults involves a variety of factors. Guidelines vary with users’ needs and environment Author: Michael Moran PT, DPT, ScD from Aged Care NZ Issue 02 2021  Older adults may require ambulation aids for a variety of reasons, such as pain or decreased balance, strength, and endurance. Such problems typically result from some sort of degenerative process such as arthritis (eg reduced strength from pain/inactivity). Other factors include injuries (often from a fall) and surgery. An ambulatory aid can increase independence for many older adults with these problems. Practical considerations Typical ambulation aids include canes, crutches, and walkers. Selecting an ambulation aid requires the consideration of several factors, including changes in gait, weight-bearing status, falls risk, the environments that a person must negotiate; lifestyle, sensory (such as vision and hearing), cosmesis (making someone or something look acceptable), and cognition. A general rule of thumb is to select the least restrictive device (eg a cane rather than a walker) that promotes independence to the greatest extent possible. Keep in mind that an aid is of no value if the individual won’t use it. The optimal location for determining the ideal ambulation aid for older adults is in their living environments. In this context, environment means all or almost all of the places older adults typically inhabit in a normal day or week. For instance, it is unwise to select a device that aids mobility on level surfaces but hampers the use of steps. An example is a wide-base quad cane that aids a patient’s mobility in the home but has a base too large for proper use on the steps leading to or from the home. Deciding what ambulation aids best suit older adults’ needs requires an accurate assessment of individuals and their typical environments. Community based assessments often more accurately identify patient-specific issues and problems. While elders may try different ambulation aids in an institutional setting, such as a hospital or a rehabilitation facility, and may even be extensively trained in their uses, carryover to a home or community setting may be impractical or even unsafe.  Typical problems and potential solutions Surfaces (inside and outside): the most common surfaces an older adult needs to negotiate are level, inclined and elevated (steps). Sometimes an ambulation aid isn’t the solution; portable ramps or a wheelchair may offer better options. For instance, if individuals need to traverse a long. level distance, they may not have the necessary endurance. Using a wheelchair could be less stressful and help them avoid exhaustion. Walking isn’t the only concern related to the mobility of older adults. They need to possess the ability to change surface heights and levels safely. Stair glides and seat lift chairs can help previously dependent individuals become independent. Securely mounted handrails can sometimes substitute for ambulation aids for elders who can negotiate steps. It’s important that the railings be secure and installed at a height suitable for the individual requiring assistance. In most situations, having the handrail at the level of the person’s greater trochanter (near the hip) is appropriate. If a landing is adjacent to the set of steps, the railings on the landing should be level rather than on angles as they are on the steps and likewise should be situated at the height of the greater trochanter. Walking speeds: How quickly does the individual need to walk? Many times, a person’s preference determines walking speed. However, some situations, such as crossing a street with the traffic light, require travelling a given distance in a specific period of time. If ambulation aids such as walkers slow down elders so that they are unable to cross streets at a timely pace, it may be essential to consider one of several changes. The situation may require a different aid, retraining with a faster speed, such as taking the arm of another person. Functional needs while using aids: Do individuals conduct all daily activities on one level, or must they also use steps? Elders may benefit from having two of the same ambulation aids – one at the top and one at the bottom of the steps. Handrails then become the aid on the steps, but older adults don't need to carry an extra device while using the steps. Some older adults need to carry items with them as they walk. If they can use both hands, a single-hand aid such as a cane or crutch frees the other hand for carrying tasks. Different strategies are required if an elder uses both hands on ambulation aids (eg a walker or canes or crutches). Fitting ambulation aids Variations in footwear provide the most challenging problem in fitting ambulatory aids. Individuals select and wear different shoes, or sometimes no footwear at all. Slippers, shoes, boots, and other footwear can effectively change a person’s height. Aids fitted when older adults wear sneakers may be too tall for the same individuals who walk to the bathroom at night wearing nothing on their feet. While it’s uncommon, some people use a night cane or one fitted for use without footwear. Another factor to consider when fitting an ambulation aid is a change in posture. A device suited to a person walking in a flexed trunk posture may become too short if the individual can assume a more upright posture. For example, if older adults use an aid to help relieve low back pain and subsequent medical intervention, such as injections in the back, relieves the pain, it’s likely they would assume a more upright posture and the aid would need to be refitted. In some cases, the pain relief eliminates the need for an aid. Unfortunately some patients demonstrate an increased flexion posture (eg from increasing kyphosis associated with spinal osteoporosis and /or compression fractures). In such cases, height adjustment of the aid to accommodate for a shorter individual is usually necessary.  Keeping it practical and effective Needs for ambulation aids can change over time. An older adult recovering from hip replacement surgery may need a walker at first but eventually progress to walking with a cane and, ultimately, with no aid at all. In selecting ambulation aids of any kind, there are many factors to consider. Walkers are multi-legged items that can include wheels of varying heights and widths. Since inappropriate wheels can increase the energy required to move the walker on carpeted or irregular surfaces, wheel selection is critical. Usually wheels are installed on the front legs of a walker. Modification of a walker’s back legs allows some older adults to ambulate better with a wheeled walker. Tennis balls on a walker’s back legs permit them to slide more easily on some surfaces such as tile. However, the drag of the tennis balls on carpets may be more than an older adult can handle. For use on carpet and most surfaces, plastic skis on the back legs can reduce friction. While some walkers are designed for use on steps, experience proves that the added weight and difficulty of use outweigh the benefits. As previously noted, even if a walker can be used on steps in a home, it probably won’t be useful on other types of steps, such as on a bus. Also if handling the weight of a device such as a standard ‘pickup’ walker leads to fatigue, it may increase the risk of a fall. In such cases, adding wheels may allow a patient to walk functionally but avoid excessive fatigue. With some wheeled walkers, brakes may be an appropriate feature. Brakes can be an appropriate feature. Brakes can be operated by exerting downward pressure on a part of the walker or by squeezing a lever-type hand attachment. It’s important for the individual to be capable of functionally using the brakes. An increased tendency to fall may occur if elders use a brake that requires squeezing a device, causing his or hand too loose contact with the support grip.  The most commonly used crutches are axillary crutches or the kind that fit under a person’s upper arm. One problem specific to axillary crutches is that older adults tend to lean on to the part that comes up under the shoulder, especially if the crutches are too long. Placing weight on the top of the crutch this way can lead to discomfort, but a proper crutch height can effectively eliminate the problem. By design, the top of the axillary crutch will come near the individual’s underarm. If clothing is in the way, the top of the crutch may not lie squarely under the axilla and can move forward abruptly during use, possibly leading to a fall. In this case, patient education and adherence to proper technique provide the ideal solution. Another common problem with axillary crutches is that even though the length of the crutch may be correct, the handgrip can be located improperly. While variations depend on specific patient needs, the handgrip is usually placed so that the angle of the elbow is approximately 45 degrees.  Canes vary considerably in both appearance and use. Canes are meant to help individuals with balance, not individuals who have weight-bearing limitations. Canes are typically single-arm items, though an older adult may occasionally need one for each hand. Commonly called straight canes, these aids are in fact rarely straight. The top part of the cane usually has a rounded appearance. The rounded portion may serve as the hand grip, or a moulded grip may be used. Canes may have a single support leg or several, such as a quad cane with four support legs. Designs vary, but quad canes are usually grouped as those having either a narrow or wide base. While more stable than a single-leg cane, quad canes have the possible disadvantage of being too large to fit entirely on a step. One solution is to turn the quad cane sideways, but that changes the function of the hand grip. Lessons learned Over decades of working with community-based older adults, the most frequent problem encountered arises when an older adult uses an ambulation aid that was fitted for another person. While their efforts are well intentioned, local community groups that lend ambulation aids don’t usually have specialists to fit the devices to the older adults who intend to use them. Frequently, the situation may result in an older adult attempting to use an aid that is too short or too tall. Older adults sometimes also take time or money-saving shortcuts when attempting to use an aid fitted for another individual, such as a deceased spouse, or family member. Many older adults use ambulation aids. Properly chosen and fitted aids can reduce dependence and enhance independence. It’s essential for caregivers to remember that an older adult’s needs for ambulatory aids may vary over time. And the type of ambulation aid required may change as an older adult’s condition changes. Professional input can make the difference between safe and unsafe situations. Selecting an ambulation aid is usually best done by a physiotherapist, in the environment, where it will be used. This helps to assess an older adult’s willingness to use an aid and to identify common obstacles not typically seen in a clinician’s office. Author: Michael Moran PT, DPT, ScD from Aged Care NZ Issue 02 2021 Reference Tsai, H. A., Kirby, R. L., MacLeod, D. A., & Graham, M. M. (2003). Aided gait of people with lower-limb amputations: Comparison of 4-footed and 2-wheeled walkers. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 84(4), 584-591. Turning the tide on diabetes More than one in four Kwis have diabetes, and it’s estimated that another 100,000 are undiagnosed. Diabetes New Zealand represents and supports people with diabetes. They have branches across New Zealand with staff and volunteers who help people to live well with diabetes From: Aged Care New Zealand, Issue 02 2021 Our vision is that the tide will be turned on diabetes, a health condition that threatens to overwhelm New Zealand’s health system both now and in the future. Our mission is to ensure that all people living in New Zealand who are affected by, or at risk of, diabetes have access to the appropriate tools, information and support essential for their health and wellbeing. People aged 40 years or over are at increased risk of developing Type 2 diabetes, but many problems with diabetes can be prevented with early diagnosis and good management. What’s more, you can support older people in the community to take action that may prevent them from ever getting diabetes. Diet, exercise, and looking after themselves both physically and emotionally, all contribute to managing or preventing diabetes. And these tips can be applied to carers too. You are what you eat Older people with diabetes need to eat a balanced diet to help manage their blood glucose levels as well as address any other dietary issues they may have. While managing excess weight is key earlier in life, for those over 70 a little excess weight can actually reduce the risk of poor health. Malnutrition and becoming underweight is an increasing issue for older people. In the case of an older person with diabetes who is also malnourished, they will need both their diabetes medication and their diet reviewed by appropriate members of their health team. With or without diabetes, as one gets older one should drink plenty of water and maintain a good diet of breakfast, lunch and dinner every day. Unless otherwise advised by their health professional, older people should be eating meals that:

It is important to remember that diet for older people with diabetes will often be indivdualised and should always be under the supervision of their health team. Get physical Exercise is especially important for people with diabetes as exercise helps insulin lower blood glucose levels. For older people, regular weight bearing and muscle strenghtening exercise can also help prevent bone loss and, by enhancing balance and flexibility, reduce the likelihood of falling and breaking a bone. Walking is an ideal form of basic physical activity. Firstly, it’s low to medium intensity - people can be encouraged to walk briskly so they elevate their heart rate but aren’t gasping for air. It is easy on the joints, it promotes good blood flow, can be done on a whim at any time of day or night, its free; and there is no complicated equipment required. Active walking promotes good blood flow by increasing heart rate without making it pound out of the chest, and as they become more accomplished walkers they can make it more challlenging. The first and most important step is to get some good shoes to walk in, comfortable and with plenty of padding in the innersole. Support those with diabetes-related foot complications to talk with their podiatrist about shoe and sock recommendations. Although walking is easy, it is still a physical activity and should be treated as such. Remember to also promote stretching after walks, ensure good water intake and encourage getting some rest.  Best foot forward Foot care is crucial for people with diabetes, and problems with feet in old age are one of the main reasons members of your community might struggle with exercise. Fortunately, giving feet some extra care can help a lot.

For those with diabetes, high blood sugar can cause neuropathy (nerve damage) and poor blood circulation over time. It also raises infection risks, as bacteria thrive on sugar. If someone you support has nerve damage or poor cirulation in their feet you will need to take additional precautions; see www.diabetes.org.nz/complications-feet. Get them to see their doctor immediately if they get any sort of cut on their feet. Love your skin and it will love you Health professionals believe people with diabetes can reduce their chances of skin problems by taking good care of their skin and managing their diabetes properly. Here are their top tips

Emotional wellbeing also needs attention The past year has been frightening and stressful for everyone. For those who are especially vulnerable to COVID-19, including those who are older and/or with pre-existing medical conditions such as diabetes, it has been more stressful for most. Diabetes New Zealand undertook new research in October that revealed distress related to COVID-19 had been even more acute for the quarter of a million people living with Diabetes New Zealand. The good news is that the research also showed that practicing self-compassion can help reduce stress, which in turn can help with better diabetes management, improve overall health and wellbeing and also mental health. The simplest way to assist those you support to manifest self-compassion in daily life is to discover how they already care for themselves, and then aid them to do these things when life becomes difficult. Physical – soften the body How would they care for themselves physically? Exercise, massage, warm bath, a cup of tea? Make time for these when things get tough. Mental – reduce agitation How do they care for their minds, especially when they’re under stress? Suggest meditating, reading an inspiring book, or something you know they find reassuring. Emotional – support them to soothe and comfort themselves How do you care for yourself? Pay attention to how people in your care do it for themselves. For example, they might enjoy being outdoors, writing a journal, or cooking. Relationships – connect with others How or when do they relate to others in a way that brings them genuine happiness? Perhaps they could meet with friends, send a birthday card, play a game with the grandchildren Spiritual – respecting and embracing their values What do they do to care for themselves spiritually? Maybe they pray, walk in the bush or on a beach, or take pleasure in helping others. Finding the things that help those you support to feel well helps you to support them better. And who knows – it might help you to care better for yourself too. Diabetes New Zealand Phone: 0800 342 238 Website. www.diabetes.org.nz Reference: Aged Care NZ Issue 02 2021 |

AuthorShonagh O'Hagan Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed